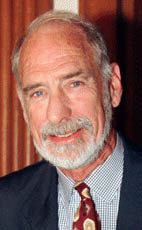

Opening Plenary Speaking Notes for the Honourable David Anderson, P.C., M.P. Minister of the Environment, Vancouver, British Columbia, May 3, 2004

Good morning everyone and welcome.

Good morning everyone and welcome.

Let me begin by thanking the co-chairs for that introduction.

On behalf of the Government of Canada and our Prime Minister, the Right Honourable Paul Martin, I want to welcome you – to Vancouver – to my home province of British Columbia – and to Canada for the Fourth World Fisheries Congress.

I am glad to be here on behalf of my colleague Geoff Regan, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, to help begin this event.

The American Fisheries Society has chosen an excellent and most appropriate venue for this congress.

This city and the coastal regions of this province have always looked to the sea. The fishery has always been a central part of life along this coast.

That is true for the Aboriginal peoples who have lived here for countless generations. It is true for people from all parts of the globe who have arrived here much more recently.

For all of us, including people like me who enjoy the sport of fishing, the health and sustainability of fish stocks matters.

Canadians, and especially those on our Pacific and Atlantic coasts, know the challenges of managing fisheries in sustainable ways.

Communities that have earned their living from the sea have seen substantial and wrenching change as traditional fish stocks have dwindled.

We have learned that the old phrase “all the fish in the sea” is no longer synonymous with unlimited resources.

But fisheries issues in Canada – as elsewhere – are not just questions of the number of fish that we can catch. They are questions that are tied to the health of the environment.

We have all learned that healthy oceans depend on the health of the lands along their coasts, the air above them and the rivers and streams that feed into them.

Fisheries issues are also about changes in our societies and economies. For example here in Canada, we have seen change as Aboriginal peoples have established their right to share in the fishery and the jobs and opportunities that it creates.

In short, oceans issues and fisheries issues are complex, high profile issues of sustainable development.

The Government of Canada knows this. We have responded by introducing much more integrated approaches to management of our fisheries and Canada’s three ocean coasts. We have seen the importance of preserving the health of the ecosystems on which fish and other aquatic species depend.

We are seeing this in work across departments of the Government of Canada, work with other levels of government and, of course, work with the stakeholders who have direct interest in all the pieces necessary to ensure a healthy, sustainable fishery.

We are seeing it in decisions such as the creation of marine protected areas and shellfish management programs.

We are seeing it in actions to address climate change and to reduce land-based sources of pollution that affect marine habitat and marine species.

These are Canadian stories. They are also the stories of many nations now.

This congress will help in the work to find those approaches – to learn from the best practices of others – to determine how best we can have the conservation that is so important and the productive fisheries on which so many people depend directly.

I should stress that it is my colleague, Minister Regan, who is responsible for fisheries management and marine conservation issues in our government. And under the conventions of parliamentary government, I do not presume to speak on his issues.

However, I can speak from my own experience.

As Chairman of the Governing Council of the United Nations Environment Programme between 2001 and 2003, I saw growing attention to oceans and fisheries issues on the international sustainable development agenda.

And I have seen the same here at home, first as Minister of Fisheries and Oceans and now, as Minister of the Environment.

In fact, I want to go back to my experience at Fisheries and Oceans because my work with our American neighbours to resolve the thorny Pacific salmon issues showed how both countries had to work together.

I can say that it certainly shows how quickly our thinking moved – and had to move.

Canada and the United States have worked together on fisheries issues for decades now – because we share so many stocks. In 1985 a new Pacific Salmon Treaty took effect to govern how we would deal with this shared resource.

However, 20 years ago, salmon stocks were taken for granted. The primary issue was allocation among fishing communities along the Pacific coast, not conservation of the salmon themselves.

It was not long before we saw the fundamental problem. Both countries managed key fisheries based on catch share “ceilings”.

Each side saw the ceiling as a quota or guarantee, and both had the right to fish whether the stocks could sustain that level of harvest or not. When abundance turned out to be lower than predicted, whoever had first crack at the fish got their ‘guaranteed’ fish. That left fishing fleets further down the salmon migration path with two choices over-fishing or not fishing at all.

The process of fixing that problem took years and a great deal of effort. It meant getting past the notion of catch ceilings and moving to a focus on cooperation, conservation and effective bilateral management of salmon.

There were many phases to this process. There were many dead-ends along the way. However, as the reality of the situation became clear to all, there was room and commitment to get this issue resolved.

One key step was domestic action to show that we were serious within our own borders. In 1998, we tackled the underlying structural issues that meant an unsustainable fishery by moving to selective harvesting techniques. We moved to a system based on 12 principles to guide management of the Pacific salmon fishery in Canadian waters.

We moved quickly from asking how to maximize the catch at any cost, to emphasizing a harvest of only those stocks that can sustain it, while allowing weaker stocks to pass through to their spawning beds.

That domestic commitment helped to set the stage for the final stage of negotiation one that achieved a breakthrough on harvesting agreements with the U.S., by focusing on conservation instead of allocation.

It was a complicated process. We had to work with the United States Government, of course. But we also had to work with the state governments of Alaska, Washington and Oregon as well as tribal governments.

All governments had to take into account the stakeholders – particularly the people and companies in the salmon fishery on both sides of the border.

There was give and take, as there always is. However, all partners in the agreement could see the reality that the old system was broken and there was no fixing it. Everyone understood that it was time to build a system based on conservation first not a race to catch the last salmon as if it were some kind of legal right.

We did it and it is working. Many salmon stocks have demonstrated renewed strength. Mortality from fishing activity – whether through by-catch or non-directed fisheries is down sharply.

Stakeholders in the fishery in both Canada and the United States have adapted to the new system. Our scientific knowledge for better management is expanding rapidly.

That story is not unique, as you all know. Around the world, fisheries are under stress. Around the world, governments and the people and businesses that depend on fisheries are trying to find answers.

Your congress is part of that effort. The extensive and interesting range of topics that I see on your agenda shows the global scale of the issues and the range of perspectives that deserve to be taken into account.

None of this is simple. But it can be done. It has to be done.

Your work here in Vancouver is a valuable contribution to improving the health of fisheries around the world and to meeting the long-term needs of the communities that depend on those fisheries.

I want to thank you and congratulate you for the time and effort that you are dedicating to the complex and important issue of fisheries management and marine conservation. I know that you will take advantage of this congress to network, develop relationships and share experiences – from which all will benefit.

Thank you.